*A Note from the Senior Editors of Marion Watch:

With deep concern for our community, we share the following information, compiled over months of careful work. Please know that gathering this was difficult, and there is more that needs to be understood. We believe these sensitive issues must be brought into the light with compassion, because ignoring the darkness allows harm to continue unchallenged. We have lost so many to addiction and predatory behavior already. We will investigate any case with ethics violations and we may recruit our national team to correspond or possibly even write with us on these subjects. They are experts in dealing with this type of behavior specifically.

As we told you when we resumed publishing, our purpose is to use our national and local alliances to gently but firmly look into serious problems affecting people’s lives. This includes examining ethical issues that could, heartbreakingly, contribute to the tragedy of deadly overdoses. We undertake this difficult work because we believe ethics and integrity matter profoundly, especially when it comes to protecting vulnerable individuals and fostering healing within our community. We have spent weeks speaking with our inner circle who have a mental health background. Parts of those screenshots are below.

Navigating Ethical and Legal Complexities in Addiction Recovery: An Analysis of Standards, Breaches, and Oversight

I. Introduction: The Criticality of Ethical and Legal Standards in Addiction Recovery

Addiction recovery centers operate at the intersection of healthcare, behavioral science, and profound human vulnerability. Individuals seeking treatment for substance use disorders (SUDs) often present with complex needs, including co-occurring mental health disorders 1, histories of trauma 1, and the heavy burden of societal stigma.3 This inherent vulnerability underscores the absolute necessity for stringent ethical and legal safeguards within treatment environments. The therapeutic relationship, built on a foundation of trust and safety, is the cornerstone of effective recovery.5 Clients must feel secure enough to engage in the difficult work of confronting addiction, exploring underlying issues, and developing coping mechanisms.

However, this essential foundation is fragile. Ethical breaches, such as inappropriate staff-client relationships, boundary violations, staff misconduct involving substance use, and failures in organizational oversight, pose a significant threat to the recovery process. Such breaches represent more than mere deviations from professional norms; they constitute profound violations of trust that can inflict substantial harm, potentially re-traumatize individuals, and significantly increase the risk of relapse.7 The very nature of addiction, involving alterations in brain circuitry related to reward, stress, and executive function, makes individuals particularly susceptible to the negative impacts of ethical failures.10 The emotional distress, instability, and introduction of triggers resulting from misconduct can derail therapeutic progress and undermine hard-won sobriety.9 This report provides a comprehensive analysis of the prevalent legal and ethical challenges within addiction recovery centers, encompassing both licensed treatment facilities and certified recovery housing environments. It examines the specific types of misconduct and oversight failures that can occur, beginning with the local context of Marion, Ohio, then expanding to the regulatory landscape of Ohio, including requirements set forth by the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services (OhioMHAS) and professional licensing boards. The analysis further broadens to incorporate nationwide ethical standards promulgated by major professional organizations and explores trends in legal liability across the United States. Crucially, this report integrates addiction science literature to explain why specific ethical breaches are fundamentally detrimental to the recovery process, disrupting therapeutic mechanisms and increasing relapse vulnerability. Finally, it analyzes the critical role of robust oversight, clear policies, comprehensive training, vigilant supervision, and safe reporting mechanisms in preventing violations and ensuring client safety. The overarching argument presented is that upholding rigorous ethical and legal standards is not simply a matter of compliance but an indispensable component of effective addiction treatment and client protection. While individual misconduct is a serious concern, systemic weaknesses within facilities—such as inadequate training, poor supervision, ambiguous policies, or a culture that fails to prioritize ethical conduct—can create environments where breaches are more likely to occur or go unaddressed.1 Therefore, ensuring ethical practice requires a multi-faceted approach involving vigilance and accountability at the individual, organizational, and systemic levels. Protecting the vulnerable individuals seeking help demands nothing less.

II. Common Ethical and Legal Challenges in Recovery

Centers

Addiction recovery settings, due to the nature of the therapeutic relationship and the vulnerability of the client population, are susceptible to a range of ethical and legal challenges. These challenges often revolve around the maintenance of professional boundaries, appropriate conduct of staff, protection of client rights, and honest operational practices.

Inappropriate Staff-Client Relationships

A fundamental ethical obligation is maintaining appropriate professional boundaries to prevent exploitation and harm. This is particularly critical regarding relational boundaries.

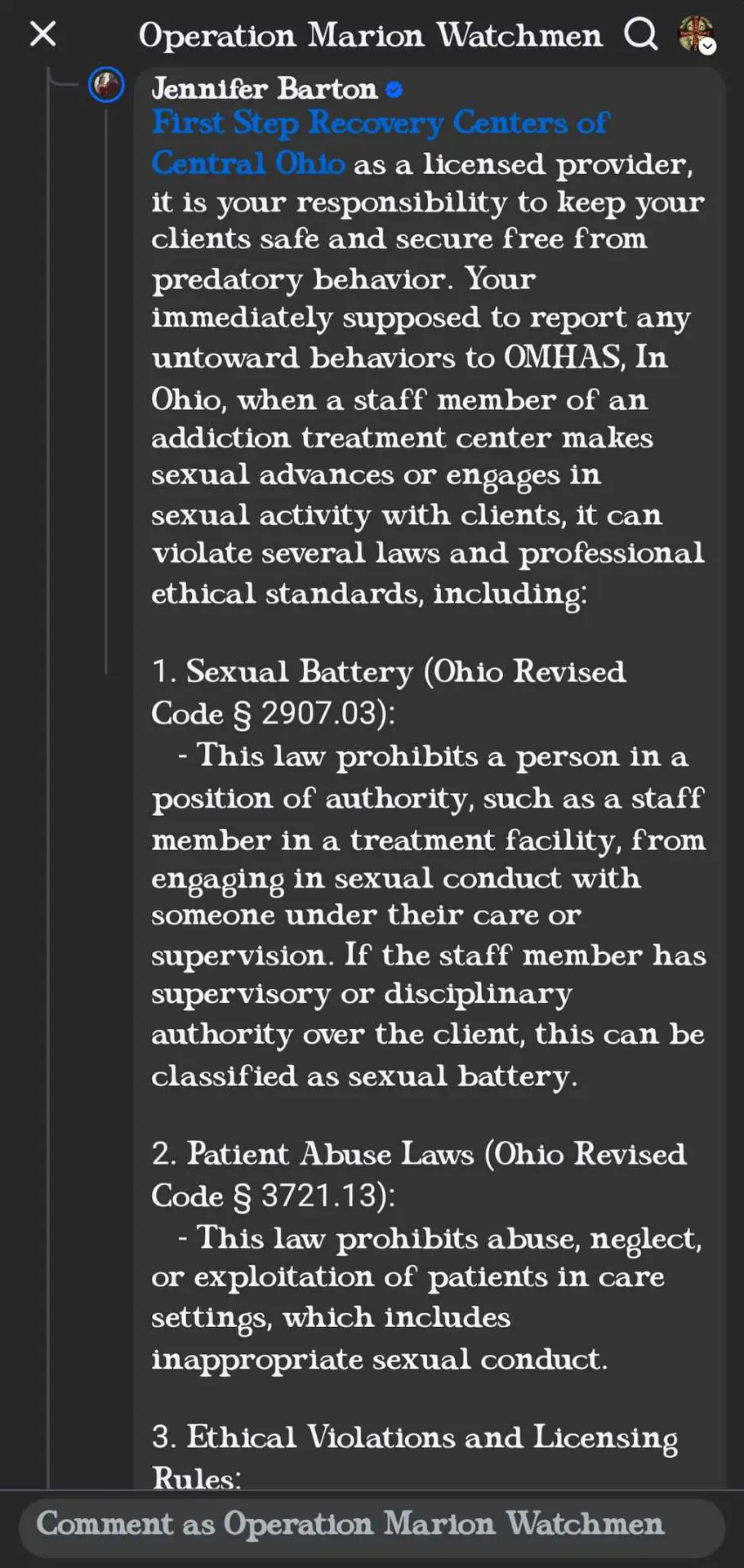

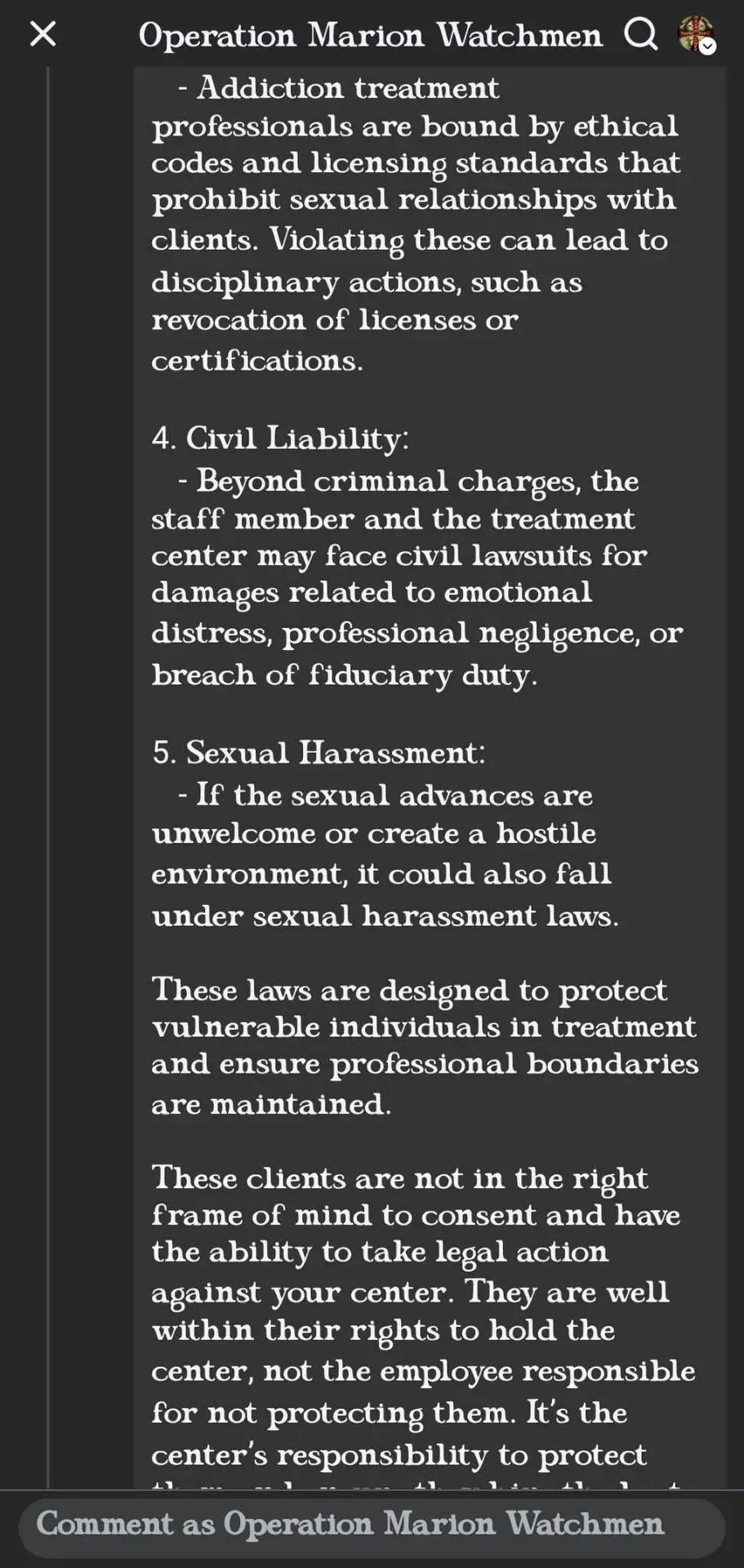

- Sexual/Romantic Relationships: Ethical codes across all major mental health and addiction professions universally prohibit sexual or romantic relationships between professionals and current clients.15 This prohibition is absolute, regardless of client consent, recognizing the inherent power imbalance and potential for exploitation.7 The prohibition often extends to relationships with clients’ relatives or close associates if there is a risk of exploitation or harm to the client.16 Post-termination relationships are also heavily restricted. Codes typically mandate a waiting period (ranging from two to five years depending on the specific code) after the last professional contact before any such relationship can even be considered.15 Even after this period, the burden of proof falls squarely on the professional to demonstrate that the relationship is not exploitative or harmful, considering factors like the duration of therapy, client vulnerability, and the circumstances of termination.15 Engaging in such relationships violates the core principles of trust and non-maleficence that underpin the therapeutic endeavor.21

- Dual/Multiple Relationships: These occur when a professional holds two or more roles simultaneously or sequentially with a client (e.g., therapist and friend, therapist and business partner, therapist and supervisor).15 Ethical codes generally caution against or prohibit dual relationships when there is a risk of client exploitation, potential harm, or impairment of the professional’s objectivity and judgment.15 This includes relationships formed through social media platforms.15 In situations where dual relationships are unavoidable (e.g., small rural communities), professionals must take specific precautions: engaging in informed consent discussions with the client about the potential risks, seeking consultation or supervision, setting clear and culturally sensitive boundaries, and meticulously documenting the rationale for continuing the relationship and how it serves the client’s best interest.15 Importantly, ethical guidelines often stipulate that any individual receiving services from an agency or facility is considered a client of all professionals employed or contracted there, for the purpose of evaluating dual relationships, not just the primary therapist.15 Local Treatment Centers Called Into Question:

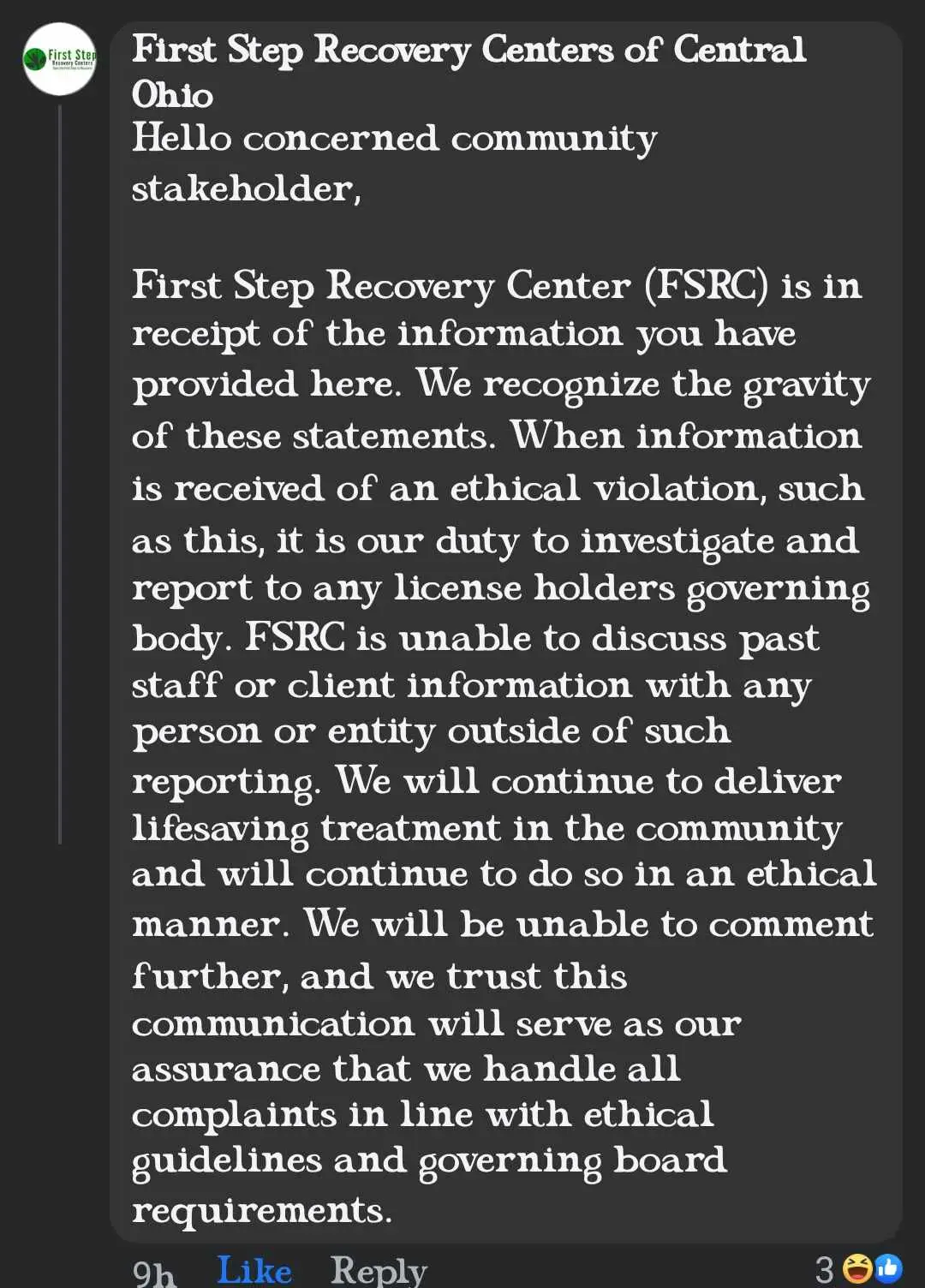

The allegations concerning the conduct of Bayley Allen, a former employee of First Step Recovery, occur against a backdrop of established ethical and legal standards governing addiction treatment. These standards, detailed in this document, emphasize the crucial need for trust, safety, and clear professional boundarie, given the vulnerability of individuals seeking help. This is a trend in the recovery community and most psychology experts we’ve been in contact agree that this nationwide issue could be due to lack of mental health services. Oftentimes addicts quit the drugs, but fail to heal the mind. This may be a case of this. The following timeline, derived from the provided letter, places the specific allegations within this ethical framework:

- During 2024: A client was undergoing treatment at First Step Recovery and residing in associated sober living housing. This period falls under the established requirement for recovery centers to maintain stringent safeguards.

- Shortly after meeting (within 2024): An alleged inappropriate relationship began between the client and First Step employee Bayley Allen. This alleged relationship involved encounters at Ms. Allen’s private residence, reportedly including drinking, sexual activity, and drug use. There may have been encounters within First Step Recovery owned houses. We have seen all texts and other material concerning these allegations and are satisfied enough to publish. These actions, represent severe boundary violations and staff misconduct, directly contradicting ethical codes prohibiting such relationships and any substance use with clients. Allegations also mention Ms. Allen having sexual relationships with other former clients residing at her home during this time. Such conduct exemplifies prohibited dual/multiple relationships, especially challenging in residential settings, and violates the core therapeutic principles of trust and safety.

- January 1, 2025: New Ohio regulations took effect, mandating certification or accreditation for recovery housing to receive referrals from state-certified providers like First Step Recovery. This highlights the increasing regulatory scrutiny on recovery housing environments around the time of the alleged incidents.

- January 25, 2025: Bayley Allen was terminated by First Step Recovery.

- A letter detailing these allegations was sent, initiating the investigation discussed in the article.

Ethical and Recovery Implications:

The alleged timeline suggests conduct by Bayley Allen occurring while the individual was an active client in a vulnerable recovery stage. As outlined in the contextual analysis:

- Violation of Boundaries and Trust: The alleged relationship and activities constitute a profound breach of the trust essential for recovery. Ohio licensing boards (OCDP and CSWMFT) have strict rules against such relationships, extending restrictions even post-termination.

- Increased Relapse Risk: Introducing substance use and emotional instability through such a relationship creates high-risk situations and triggers, directly undermining recovery efforts and potentially re-traumatizing individuals.

- Oversight and Liability: The termination indicates an organizational response, but the allegations raise questions about supervision and the facility’s mechanisms for preventing such breaches. Facilities can bear legal liability for employee actions.

In essence, placing the allegations against Bayley Allen onto a timeline underscores the potential duration and severity of the ethical violations relative to the client’s treatment period. This conduct, occurring within the recovery environment and allegedly involving substance use, directly conflicts with the foundational ethical principles designed to protect clients and facilitate healing. The fact that Ms. Allen has had previous sexual relationships with others in recovery, and dwelling with at least two we are aware of is highly concerning.

Closer to Marion:

Local Treatment Centers Called Into Question:

The allegations concerning the conduct of Bayley Allen, a former employee of First Step Recovery, occur against a backdrop of established ethical and legal standards governing addiction treatment. These standards, detailed in this document, emphasize the crucial need for trust, safety, and clear professional boundaries, given the vulnerability of individuals seeking help. This is a trend in the recovery community and most psychology experts we’ve been in contact agree that this nationwide issue could be due to lack of mental health services. Oftentimes addicts quit the drugs, but fail to heal the mind. This may be a case of this. The following timeline, derived from the provided letter, places the specific allegations within this ethical framework:

- During 2024: A client was undergoing treatment at First Step Recovery and residing in associated sober living housing. This period falls under the established requirement for recovery centers to maintain stringent safeguards.

- Shortly after meeting (within 2024): An alleged inappropriate relationship began between the client and First Step employee Bayley Allen. This alleged relationship involved encounters at Ms. Allen’s private residence, reportedly including drinking, sexual activity, and drug use. There may have been encounters within First Step Recovery owned houses. We have seen all texts and other material concerning these allegations and are satisfied enough to publish. These actions, represent severe boundary violations and staff misconduct, directly contradicting ethical codes prohibiting such relationships and any substance use with clients. Allegations also mention Ms. Allen having sexual relationships with other former clients residing at her home during this time. Such conduct exemplifies prohibited dual/multiple relationships, especially challenging in residential settings, and violates the core therapeutic principles of trust and safety.

- January 1, 2025: New Ohio regulations took effect, mandating certification or accreditation for recovery housing to receive referrals from state-certified providers like First Step Recovery. This highlights the increasing regulatory scrutiny on recovery housing environments around the time of the alleged incidents.

- January 25, 2025: Bayley Allen was terminated by First Step Recovery.

- Approx. :: A letter detailing these allegations was sent, initiating the investigation discussed in the article.

Ethical and Recovery Implications:

The alleged timeline suggests conduct by Bayley Allen occurring while the individual was an active client in a vulnerable recovery stage. As outlined in the contextual analysis:

- Violation of Boundaries and Trust: The alleged relationship and activities constitute a profound breach of the trust essential for recovery. Ohio licensing boards (OCDP and CSWMFT) have strict rules against such relationships, extending restrictions even post-termination.

- Increased Relapse Risk: Introducing substance use and emotional instability through such a relationship creates high-risk situations and triggers, directly undermining recovery efforts and potentially re-traumatizing individuals.

- Oversight and Liability: The termination indicates an organizational response, but the allegations raise questions about supervision and the facility’s mechanisms for preventing such breaches. Facilities can bear legal liability for employee actions.

In essence, placing the allegations against Bayley Allen, or as a general practice when investigating, onto a timeline underscores the potential duration and severity of the ethical violations relative to the client’s treatment period. This conduct, occurring within the recovery environment and allegedly involving substance use, directly conflicts with the foundational ethical principles designed to protect clients and facilitate healing. The fact that Ms. Allen has had previous sexual relationships with others in recovery, and dwelling with at least two we are aware of is highly concerning.

Boundary Violations in Practice

The concept of boundaries in therapy refers to the limits that define the therapeutic relationship, ensuring it remains safe, professional, and focused on the client’s needs.

- Boundary Crossings vs. Violations: A critical distinction exists between boundary crossings and boundary violations.23 A boundary crossing is a deviation from usual practice that is generally harmless, non-exploitative, and potentially even helpful to the therapy (e.g., accepting a small token gift, briefly self-disclosing non-intimate information for therapeutic benefit). A boundary violation, conversely, is a harmful or exploitative deviation that compromises the therapeutic relationship and client welfare (e.g., engaging in sexual intimacy, exploiting the client financially, forming a social relationship that impairs objectivity).23 The “slippery slope” concept posits that minor, seemingly benign boundary crossings can sometimes incrementally lead to more serious violations if not carefully managed.25 Navigating this requires careful judgment, as rigid avoidance of all crossings might create a sterile therapeutic environment, while inappropriate crossings risk harm.26 The key determinant is whether the action prioritizes the client’s welfare and therapeutic goals or serves the professional’s needs.26

- Challenges in Residential Settings: Recovery housing and residential treatment facilities present unique boundary challenges.28 The 24/7 nature of these settings, shared living spaces, and the potential for staff to fulfill multiple roles (e.g., therapist, house manager, mentor, rule enforcer) increase the opportunities for blurred lines and dual relationships.28 The close proximity can foster intense transference and countertransference dynamics. Ohio’s specific regulations for recovery housing emphasize the need for clear protocols, quality standards, and adherence to ethical codes.29 Notably, the Ohio Chemical Dependency Professionals Board’s code explicitly states that residents in recovery housing are considered clients for the purpose of boundary regulations, reinforcing ethical obligations in this specific context.15 This heightened risk necessitates specific policies, clear role definitions, and targeted staff training for residential environments.

- Self-Disclosure: While some self-disclosure by a therapist can be therapeutically beneficial if used judiciously, excessive or inappropriate self-disclosure (e.g., sharing personal problems, intimate details) is a boundary crossing that can become a violation.23 It can shift the focus away from the client, confuse the therapeutic roles, potentially burden the client, and interfere with the therapeutic process due to complex transference issues.21

- Gifts: Accepting gifts from clients can complicate the therapeutic relationship and potentially constitute a dual relationship.31 Ethical codes advise professionals to consider the therapeutic context, the gift’s monetary value, the client’s motivation for giving, the professional’s motivation for accepting or declining, and cultural norms.31 While refusing a small token of appreciation might sometimes harm rapport, accepting valuable gifts or gifts intended to manipulate is generally unethical.31 Clear agency policies regarding gifts are recommended to guide staff and manage expectations.31

Staff Substance Use and Misconduct

The conduct of staff members, particularly regarding substance use and impairment, is a critical ethical concern.

- Impairment: Professionals have an ethical obligation to refrain from practice when their own physical, mental, emotional, or substance-related problems could impair their judgment, competence, or objectivity.15 They are expected to recognize signs of impairment in themselves, seek appropriate assistance, and potentially limit or suspend their professional activities (e.g., request inactive status) if necessary to protect clients.15

- Facilitating Client Substance Use: Any instance of staff providing, condoning, or using alcohol or illicit drugs with clients represents a egregious ethical violation and a fundamental betrayal of the treatment mission. This directly undermines recovery efforts and constitutes serious misconduct.

- General Misconduct: This encompasses a range of unethical and potentially illegal behaviors, including physical, emotional, or sexual abuse; neglect of client needs; financial exploitation; fraud (e.g., billing for services not rendered); and harassment.15

Confidentiality and Informed Consent

These two principles are foundational to ethical practice and client rights.

- Confidentiality: Protecting client privacy is paramount for building trust and encouraging open communication.5 Federal laws like HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) and 42 CFR Part 2 (specific to substance use disorder records) impose strict requirements.6 Professionals must explain the scope and limits of confidentiality to clients at the outset of treatment, including mandatory reporting exceptions (e.g., imminent harm to self or others, child or elder abuse).5 Breaches can occur through careless conversations, insecure storage of records (physical or electronic), or unauthorized disclosures.6 Special attention is needed in group therapy settings 41 and when using telehealth technologies.5

- Informed Consent: This is more than just obtaining a signature; it is an ongoing process of communication ensuring clients understand their treatment.5 Clients must be informed about the nature of services, potential risks and benefits, treatment alternatives (including no treatment), costs and billing, confidentiality limits, and their right to refuse or withdraw consent at any time.5 Information must be provided in clear, understandable language, considering the client’s developmental level, cognitive capacity, and cultural background.5 Specific procedures apply when clients lack the capacity to consent (e.g., minors, incapacitated adults), involving assent from the client and consent from a legally authorized representative.17

Exploitative Practices

Beyond individual clinical interactions, ethical issues can arise from organizational practices.

- Patient Brokering: This involves paying or receiving kickbacks for client referrals.47 It prioritizes financial gain over client welfare and clinical appropriateness, is widely considered unethical, and is illegal in many jurisdictions. This can sometimes involve “addiction tourism,” where patients are recruited from other states.47 OhioMHAS Quality Housing Criteria explicitly prohibit brokering for recovery residences.48

- Misrepresentation of Services: Making false or misleading claims in marketing materials about the types of services offered, facility accreditation, staff credentials, success rates, or affiliations is unethical and deceptive.47

- Insurance Fraud: Practices like billing insurance companies for services not rendered or performing and billing for excessive, medically unnecessary procedures (e.g., frequent, high-cost urine drug screens without clinical justification) constitute fraud.47

III. The Local Landscape: Marion, Ohio

Examining the specific context of Marion, Ohio, provides a localized perspective on the broader issues of ethical and legal standards in addiction recovery services.

Overview of Local Services

Marion County offers a range of resources for individuals struggling with addiction and mental health issues. Services available include counseling and behavioral health services, specific drug and alcohol addiction treatment programs, emergency and crisis intervention, recovery housing options, and various support groups.50 Many of these services are planned, funded, or monitored through the local Alcohol, Drug Addiction, and Mental Health (ADAMH) Board.50

Notable local initiatives reflect efforts to address the opioid crisis. The Marion County Prosecutor’s Intervention Program (PIP), started in 2022, offers treatment and counseling as an alternative to indictment for low-level felony drug offenders and has reported success in reducing overdose deaths.54 Additionally, efforts were underway as of 2017 to establish a dedicated detox center in Marion to meet community needs.55 Veterans in the area can also access mental health and potentially addiction-related services through the Marion VA Clinic.56 Various state and local agencies provide referral information and support.51

Reported Concerns/Incidents in Marion

The research materials reviewed for this report did not reveal specific, publicly documented instances of major ethical scandals, widespread complaints, or systemic failures within Marion’s addiction recovery centers. News reports highlighted positive initiatives like the PIP program 54 and the development of new facilities.55

However, the absence of such public reports does not necessarily indicate an absence of problems. Ethical breaches may be handled internally, go unreported by clients or staff, or may not have reached a threshold to garner media attention or public investigation. Furthermore, Marion operates within a statewide context where concerns about the addiction treatment industry, particularly recovery housing, have been explicitly raised. State Representative Riordan T. McClain Pizzulli characterized Ohio’s recovery housing industry as operating in a “Wild West” environment lacking adequate oversight and allowing “bad actors to exploit the system”.58 This statewide concern led to the introduction of legislation (HB 33) aimed at strengthening oversight, including establishing certification requirements and empowering local ADAMH boards.58 Issues like uneven distribution of recovery housing (with some counties exceeding 500% capacity while 21 counties had none) were also noted statewide.58 Representative Pizzulli’s office explicitly solicited testimony and created a form for individuals to report concerns about recovery homes in their area 58, indicating an official channel for addressing potential issues that might exist in communities like Marion. Therefore, while specific Marion-based crises were not identified in the provided data, the statewide regulatory push suggests that vulnerabilities potentially affecting Marion were recognized at the state level.

Local Oversight: Marion-Crawford ADAMH Board

The primary local entity responsible for overseeing publicly funded mental health and addiction services in Marion County is the Crawford-Marion ADAMH Board.50

- Role and Responsibilities: The Board’s mission is to ensure the availability of high-quality alcohol, drug addiction, and mental health services for residents through planning (needs assessment, priority setting), purchasing cost-effective services, monitoring service quality, and evaluating outcomes.50 They play a crucial role in coordinating the local continuum of care.

- Activities and Partnerships: The ADAMH Board funds various services, including medication, case management, day treatment, crisis services, Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) support, and counseling.52 It collaborates extensively with community partners, including local courts (Common Pleas, Family, Municipal), probation departments, law enforcement, and consumer advocacy groups like the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI).52 The Board is subject to financial audits by the state.60

- Oversight and Complaints: The ADAMH Board monitors the services it funds.52 While OhioMHAS provides a statewide complaint mechanism for licensed/certified providers 61, ADAMH boards typically serve as a local point of contact for client rights issues and grievances related to the agencies they fund.62 They usually designate a Client Rights Officer (CRO) to handle complaints and ensure providers adhere to client rights regulations (like OAC 5122-26-18).62 Furthermore, recent legislative proposals aim to grant local ADAMH boards direct authority to inspect recovery housing facilities, investigate complaints related to them, and impose penalties for non-compliance.58 This positions the Marion-Crawford ADAMH Board as a critical node for local oversight, particularly as new state regulations for recovery housing take effect. Contact information for the Board is publicly available.50

The effectiveness of local oversight in Marion hinges significantly on the capacity, resources, and diligence of the Marion-Crawford ADAMH Board, especially in navigating the evolving regulatory landscape for recovery housing and ensuring adherence to ethical standards among funded providers.

IV. Ohio’s Regulatory Framework for Addiction Treatment

The State of Ohio employs a multi-faceted regulatory framework to govern addiction treatment centers and recovery housing, primarily through the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services (OhioMHAS) and specific sections of the Ohio Administrative Code (OAC) and Ohio Revised Code (ORC).

Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services (OhioMHAS) Certification

OhioMHAS is the primary state agency responsible for certifying providers of mental health and addiction services.64 Certification requires adherence to a comprehensive set of rules outlined primarily in OAC Title 5122.

- Personnel Standards (OAC 5122-29-30): This rule defines who is eligible to provide and supervise certified behavioral health services based on their professional scope of practice, licensure, certification, or registration.66 It mandates compliance with relevant licensing board requirements regarding scope of practice, supervision, and ethics.66 Crucially, it establishes standards for unlicensed staff performing specific services (like SUD case management, CPST, therapeutic behavioral services). These individuals, often termed Qualified Behavioral Health Specialists (QBHS), must receive training and demonstrate minimum competencies in areas such as understanding mental illness or SUD treatment, navigating relevant service systems (behavioral health, social services, criminal justice), recognizing symptoms, therapeutic engagement, crisis response, and de-escalation techniques.66 Providers must ensure QBHS are appropriately supervised by qualified licensed professionals.66 Related Medicaid rules (OAC 5160-27-01) also reference these standards.65

- General Service Requirements (OAC 5122-29-03): This rule outlines the basic types of general services offered by certified providers, including assessment activities (diagnostic evaluation, treatment planning), medical activities (prescribing, managing, administering medication), and counseling and therapy activities.67

- Specific Service Rules: OhioMHAS maintains specific rules detailing requirements for various certified services, such as Mental Health Day Treatment (OAC 5122-29-06) 68, SUD Case Management (OAC 5122-29-13) 66, Community Psychiatric Supportive Treatment (CPST) (OAC 5122-29-17) 66, Intensive Home Based Treatment (IHBT) (OAC 5122-29-28) 66, and Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) (OAC 5122-29-29).66

Client Rights and Grievance Procedures (OAC 5122-26-18)

This rule establishes robust protections for individuals receiving services from OhioMHAS-certified agencies.70 Its specificity indicates a strong regulatory emphasis on client empowerment and accountability.

- Mandates: Every certified provider must develop and implement a written client rights policy and a formal grievance procedure.62 These documents must be posted prominently in service locations (where feasible) and must be provided in writing and explained verbally to clients in understandable terms.70

- Enumerated Rights: The rule lists specific client rights, including, but not limited to:

- Treatment with consideration, respect for dignity, autonomy, and privacy.70

- Reasonable protection from physical, sexual, or emotional abuse, neglect, and inhumane treatment.70

- Services in the least restrictive, feasible environment.70

- Participation in the development, review, and revision of their individualized service plan.70

- Freedom from unnecessary/excessive medication, restraint, or seclusion (unless imminent risk of harm exists).70

- Informed consent for, and the right to refuse, any service, procedure (especially unusual/hazardous ones), or observation.70

- Confidentiality of information and records.70

- Knowledge of service costs.70

- The right to file a grievance without fear of reprisal.70

- Access to one’s own records (subject to certain limitations and procedures).70

- Grievance Procedure Requirements: The rule defines a “grievance” as a complaint regarding the denial or abuse of any client right.62 Providers must designate a Client Rights Officer (CRO) or advocate responsible for handling grievances.62 The procedure must allow grievances to be filed verbally or in writing, provide assistance with filing if requested, ensure prompt investigation (immediate for abuse/neglect allegations), and aim for resolution typically within 20 business days.62 The process must be documented, including the grievance, investigation steps, resolution, and any reasons for delay.70 Clients must be informed of appeal options if unsatisfied (e.g., contacting the local ADAMH Board, OhioMHAS, Disability Rights Ohio).62 Records of grievances must be maintained for at least two years.70

Incident Reporting Mandates

OhioMHAS requires certified providers to report significant incidents affecting client health and safety.

- System Requirement: Providers must establish an internal incident reporting system that includes mechanisms for review and analysis aimed at identifying risks and implementing corrective actions to prevent recurrence.73

- Incident Categories: Regulations distinguish between “Reportable Incidents” (serious events requiring immediate notification, previously termed Major Unusual Incidents or MUIs) and “Six Month Reportable Incidents” (less severe incidents reported in aggregate).73 While OAC 5122-26-13 (community agencies) and 5122-14-14 (psychiatric hospitals) detail the reporting requirements for MHAS-certified entities, the definitions of specific incident types (like abuse, neglect, exploitation) may align with frameworks like those in OAC 5123-17-02 for the developmental disabilities system.39 Reportable incidents typically include events like death, abuse/neglect, exploitation, significant injury, medication errors causing harm, missing persons at risk, and certain types of physical altercations.40

- Reporting Timelines and Process: Reportable incidents must typically be documented internally within 24 hours of discovery.73 These reports must then be forwarded electronically (e.g., via the WEIRS system) to OhioMHAS (and the relevant ADAMH Board for community agencies) within 24 hours, excluding weekends and holidays.73 Six-month summary data reports are due semi-annually.73 OhioMHAS may initiate further investigation based on these reports.73

- Mandatory Reporting of Abuse/Neglect: Separate from the OhioMHAS incident reporting system, Ohio law mandates immediate reporting of suspected child abuse or neglect to the county children services board or law enforcement (ORC 2151.421) 43, and suspected abuse, neglect, or exploitation of an adult (particularly elderly or disabled) to appropriate authorities (e.g., county JFS, law enforcement).43 Failure to make these legally mandated reports is a serious offense.39

Regulation and Oversight of Recovery Housing

Recognizing the unique nature and potential vulnerabilities of recovery housing, Ohio has implemented specific regulations distinct from, but complementary to, general behavioral health certification. This reflects an understanding that the non-clinical, peer-support-oriented, residential model of recovery housing requires tailored standards and oversight.

- Legal Framework: Ohio Revised Code sections 340.034 and 5119.39 through 5119.397 provide the statutory basis for recovery housing regulation.75

- OhioMHAS Role: OhioMHAS is tasked with monitoring the establishment and operation of recovery housing residences statewide.59 This includes maintaining a statewide registry of residences and establishing procedures for handling complaints and conducting investigations related to recovery housing.59

- Registration and Certification Mandate: All recovery housing residences operating in Ohio must register with OhioMHAS.59 A significant change took effect January 1, 2025: only residences that are appropriately accredited or certified and listed on the OhioMHAS registry are permitted to receive referrals from OhioMHAS-certified community behavioral health providers, receive designated state funding, or advertise themselves as recovery housing, sober living, or similar entities.29 Ohio Recovery Housing (ORH), the state affiliate of the National Alliance for Recovery Residences (NARR), is the primary entity responsible for certifying recovery homes in Ohio based on NARR standards and specific Ohio “measures”.29

- Quality Standards and Protocols: Recovery residences must comply with OhioMHAS monitoring requirements and any associated rules.75 They are required to have established protocols covering administrative oversight, quality standards, and operational policies and procedures, including house rules for residents.75 OhioMHAS has published “Quality Housing Criteria” that outline expectations for safety (including annual fire inspections, smoke/CO detectors, extinguishers), physical structure (protection from elements, freedom from hazards), physical space (privacy, occupancy limits – generally max 2 adults/bedroom, max 16 adults/single-family structure unless exception granted, minimum square footage per person/unit), sanitation, non-discrimination, and a strict prohibition against patient brokering.48 ORH certification involves a rigorous review process including assessment of policies/procedures, staff/resident interviews, and detailed dwelling inspections checking for safety features (e.g., naloxone availability), cleanliness, adequate space (including food storage), and a home-like environment.29 Adherence to the NARR Code of Ethics is also a requirement for ORH certification.29

- Resident Rights and Policies: State law mandates that recovery residences cannot limit a resident’s length of stay to an arbitrary fixed time; duration should be based on individual needs, progress, and adherence to house rules, determined collaboratively.75 Residences must permit residents to receive Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT).75 They may allow residents’ family members to reside with them if permitted by house protocols.75 Residents may also receive certified addiction services while living in the residence.75

Summary of Key Ohio Regulations Governing Addiction Treatment and Recovery Housing

Provider Certification

- Relevant OAC/ORC Rule(s): OAC 5122-24 to 5122-29

- Key Requirements: Must follow rules regarding governance, services offered, personnel qualifications, record-keeping, facility safety, and other operational aspects. Specific rules apply depending on the type of service provided (e.g., counseling, case management, Assertive Community Treatment (ACT), Intensive Home-Based Treatment (IHBT)).

- Oversight Body: Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services (OhioMHAS)

Personnel Standards

- Relevant OAC/ORC Rule(s): OAC 5122-29-30

- Key Requirements: Specifies which licensed professionals are eligible to provide and supervise services based on their scope of practice. Establishes standards for unlicensed staff, such as Qualified Behavioral Health Specialists (QBHS), including required training, competency levels, and supervision protocols.

- Oversight Body: OhioMHAS, Professional Licensing Boards

Client Rights

- Relevant OAC/ORC Rule(s): OAC 5122-26-18

- Key Requirements: Requires providers to have a written policy on client rights. These rights must be posted and explained to clients, covering areas like respectful treatment, safety, participation in care planning, the right to refuse services, confidentiality, and others. A formal grievance procedure must be established, including a designated Client Rights Officer (CRO), specific timelines for addressing grievances, documentation requirements, and an appeals process.

- Oversight Body: OhioMHAS, Alcohol, Drug Addiction, and Mental Health Services (ADAMH) Boards

Incident Reporting

- Relevant OAC/ORC Rule(s): OAC 5122-26-13 (Community Providers), OAC 5122-14-14 (Hospital Settings)

- Key Requirements: Providers must implement an internal system to review and analyze incidents. Certain significant events, defined as “Reportable Incidents,” must be reported to OhioMHAS and the relevant ADAMH Board within 24 hours (excluding weekends and holidays). Providers must also submit aggregate data on these incidents in a “Six Month Reportable Incident” report twice a year. Note that separate mandatory reporting laws (ORC) apply specifically to suspected child or elder abuse/neglect.

- Oversight Body: OhioMHAS, ADAMH Boards

Recovery Housing

- Relevant OAC/ORC Rule(s): ORC 340.034, 5119.39-5119.397; OAC 5119 rules (pending)

- Key Requirements: Requires registration with OhioMHAS. As of January 1, 2025, certification or accreditation through Ohio Recovery Housing (ORH) / National Alliance for Recovery Residences (NARR) is mandatory for receiving referrals, funding, or advertising services. Must establish protocols for oversight and maintain quality standards based on NARR principles, including clear policies and house rules. Must permit residents to use Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) and base length of stay on individual need, not arbitrary time limits. Must adhere to OhioMHAS Quality Housing Criteria covering safety, adequate space, sanitation, non-discrimination policies, and prohibiting patient brokering.

- Oversight Body: OhioMHAS, Ohio Recovery Housing (ORH), ADAMH Boards (with a potentially expanding role)

V. Ethical Codes of Ohio Professional Licensing Boards

In addition to OhioMHAS certification rules, individual professionals providing addiction treatment services in Ohio are governed by the ethical codes enforced by their respective licensing boards. The two most prominent boards for addiction professionals are the Ohio Chemical Dependency Professionals (OCDP) Board and the Counselor, Social Worker, and Marriage and Family Therapist (CSWMFT) Board. While sharing core ethical principles, their specific rules contain nuances critical for compliance.

Ohio Chemical Dependency Professionals (OCDP) Board (OAC 4758-8-01)

The OCDP Board’s Code of Ethics 15 provides detailed standards for chemical dependency counselors, assistants, prevention specialists, and supervisors.

- Multiple Relationships: The code prohibits multiple relationships (familial, social, financial, supervisory, etc.) if they might impair professional judgment, increase exploitation risk, or are not in the client’s best interest. Financial relationships include accepting gifts, bartering, or offering free services/discounts. For unavoidable multiple relationships, dependent licensees must discuss with their supervisor and client, obtain written consent from all parties, and document the rationale prioritizing client interest. Independent licensees must consult with another independent licensee and follow similar discussion, consent, and documentation steps. Critically, this rule explicitly states that residents of recovery housing and clients of a treatment agency are considered clients of any licensee working there in any capacity, clarifying boundary expectations in these settings.15

- Sexual Conduct: There is an absolute prohibition on any sexual conduct (consensual or not) with current clients. Providing services to individuals with whom the licensee has had a prior sexual relationship is also forbidden. A minimum two-year waiting period applies after termination of professional services before any sexual relationship with a former client can be considered, and even then, it is prohibited if not in the client’s best interest or if it increases exploitation risk. The licensee bears the burden of proving non-exploitation if such a relationship occurs after two years. Sexual relationships with a former client’s family members are prohibited if exploitative. Sexual harassment of clients, former clients, their families, or others in professional settings is forbidden.15

- Impairment: Licensees must not practice if their judgment or competence is reasonably believed to be impaired due to mental, emotional, physiological, pharmacological, or substance use conditions. They have a duty to seek professional help, consider requesting inactive status for medical reasons, or utilize the board’s confidential safe-haven program.15

- Supervision: Licensees must provide services only under appropriate supervision according to their scope of practice and must complete all required supervision documentation.15

Counselor, Social Worker, and Marriage and Family Therapist (CSWMFT) Board (OAC Chapter 4757-5)

The CSWMFT Board’s Code of Ethics applies to licensed counselors, social workers, and marriage and family therapists.

- General Conduct (OAC 4757-5-01): This foundational rule establishes that Chapter 4757-5 constitutes the standards for professional conduct, and violations can lead to disciplinary action.78 It acknowledges the ethical codes of major professional associations (ACA, NASW, AAMFT, etc.) as interpretive aids but states that the board’s rules take precedence in case of conflict.78 While setting the framework, it doesn’t explicitly detail principles like “acting in the client’s best interest” or “avoiding harm,” directing licensees to the specific rules within the chapter.78

- Multiple Relationships (OAC 4757-5-03): Licensees must avoid multiple relationships (familial, social, emotional, business, financial, supervisory, political, administrative, legal, social media) if they are not in the client’s best interest, might impair judgment, or increase exploitation risk.24 If a multiple relationship is recognized or unavoidable, the licensee must discuss it with the client, proceed only with agreement, document the relationship and its justification (client’s best interest/not harmful) in the record, continuously reassess, and consider informed consent, consultation, and supervision.24 The rule states that a client of an agency is considered a client of each licensee employed or contracted by that agency.24 Licensees are advised to decline gifts, though accepting nominal gifts may be permissible if declining harms the therapeutic process, requiring discussion and documentation justifying the acceptance.24

- Sexual Misconduct (OAC 4757-5-04): Sexual relations with current clients are strictly prohibited, regardless of consent, and this applies to all clients of the agency based on the licensee’s knowledge.16 A minimum five-year prohibition exists for sexual relations with former clients.16 After five years, the licensee bears the significant burden of examining and documenting that the relationship is not exploitative, considering numerous factors like therapy duration, time elapsed, termination circumstances, client history and mental status, potential adverse impact, power dynamics, and any prior actions by the professional suggesting post-termination intimacy.16 Sexual activity with clients’ relatives or close associates is also prohibited if there’s a risk of exploitation or potential harm to the client.16

Comparative Analysis and Implications

While both the OCDP and CSWMFT boards maintain stringent prohibitions against sexual misconduct and harmful multiple relationships, key differences exist that necessitate careful attention from licensees and employers:

- Post-Termination Sexual Relationship Waiting Period: The OCDP board mandates a 2-year minimum waiting period 15, whereas the CSWMFT board requires 5 years.16 Both emphasize that even after the waiting period, the relationship is only permissible if proven non-exploitative.

- Procedures for Unavoidable Multiple Relationships: The OCDP code specifies different procedural requirements based on license dependency (supervisor consent vs. peer consultation) 15, while the CSWMFT code outlines steps applicable to all its licensees/registrants.24

- Recovery Housing Specificity: The OCDP code’s explicit inclusion of recovery housing residents as “clients” for boundary purposes provides clearer guidance for chemical dependency professionals in that specific, high-risk setting compared to the CSWMFT code’s more general agency-based definition.15 This may reflect the unique prevalence of chemical dependency professionals in recovery housing roles and the board’s recognition of the setting’s distinct boundary challenges.

These distinctions underscore the importance for professionals holding licenses from either or both boards, as well as the facilities employing them, to be intimately familiar with the specific requirements of each applicable code. Supervisors must also be aware of these differences when overseeing supervisees with different license types.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Selected Boundary and Misconduct Rules (Ohio OCDP vs. CSWMFT Boards)

|

Ethical Issue |

OCDP Rule (OAC 4758-8-01) |

CSWMFT Rule (OAC 4757-5-03 / 4757-5-04) |

Key Similarities/Differences |

|

Current Sexual Relationship |

Prohibited (consensual or not) |

Prohibited (consensual or forced) |

Both absolute prohibition. |

|

Former Sexual Relationship |

Prohibited for min. 2 years; burden on licensee to prove non-exploitation after. |

Prohibited for min. 5 years; burden on licensee to prove non-exploitation after (detailed factors listed). |

Difference in waiting period (2 vs 5 years). Both require proof of non-exploitation. |

|

Sexual Relationship w/ Client Relatives/Associates |

Prohibited if exploitative (former client’s family). |

Prohibited if risk of exploitation or harm to client (current client’s relatives/associates). |

Similar principle, slight difference in scope (former vs. current client focus). |

|

Multiple Relationships (General) |

Avoid if impairs judgment, exploitative, or not in client’s best interest. Explicitly includes recovery housing. |

Avoid if impairs judgment, exploitative, or not in client’s best interest. |

Both prohibit harmful/exploitative relationships. OCDP rule explicitly mentions recovery housing. |

|

Managing Unavoidable Multiple Relationships |

Requires supervisor/client consent & documentation (dependent licensee) OR peer consultation/client consent & documentation (independent licensee). |

Requires client discussion/agreement, record notation/justification, ongoing reassessment, consideration of consent/consultation/supervision. |

Both require process, documentation, and focus on client interest. OCDP has license-level specific procedures. |

|

Gifts |

Included under prohibited financial multiple relationships (bartering, free services, discounts also mentioned). |

Advised to decline; nominal exception possible with justification/documentation. |

CSWMFT rule provides more specific guidance on gift acceptance. OCDP rule frames it within broader financial relationships. |

|

Social Media Boundaries |

Included as a type of multiple relationship (social media/personal virtual). |

Included as a type of multiple relationship (social media/personal virtual, including online communities). |

Both recognize social media as a potential area for boundary issues. |

|

Impairment |

Must not practice if impaired; must seek help/consider inactive status/use safe-haven. |

(Covered under OAC 4757-5-02 – Competence/Impairment, not detailed in provided snippets but generally requires similar action). |

Both boards address impairment, requiring professionals to cease practice and seek help if necessary. |

VI. Nationwide Ethical Standards and Guidelines

Beyond Ohio’s specific regulations, addiction recovery centers and professionals operate within a broader context of national ethical standards established by major professional organizations. These codes provide foundational principles and specific guidance applicable across state lines.

NAADAC (Association for Addiction Professionals) Code of Ethics (2021 Revision)

As the leading organization specifically for addiction professionals, the NAADAC Code of Ethics is highly influential.79 The 2021 revision represents a comprehensive update organized around nine core Principles.19

- Core Principles and Values: The code emphasizes the primary responsibility to ensure client safety and welfare, acting with respect, sensitivity, and compassion (Principle I-1).19 It is grounded in ethical ideals like autonomy, beneficence (helping others), non-maleficence (do no harm), justice, fidelity, honesty, and competence.80

- The Counseling Relationship (Principle I): This principle covers crucial areas including informed consent and mandatory disclosures (regarding services, credentials, confidentiality limits, technology use, fees).19 It mandates respecting client diversity and providing culturally sensitive services, prohibiting discrimination.19 Regarding boundaries, it directs professionals to avoid multiple/dual relationships whenever possible. If unavoidable, precautions like informed consent, consultation, supervision, and documentation are required to prevent impaired judgment or exploitation (I-11).19 The code explicitly prohibits sexual or romantic relationships with current or former clients, friends, or family members, including electronic interactions (I-23).19 It also cautions about the risks of accepting clients with whom a prior relationship existed (I-12) 19 and warns against exploiting client trust and dependency.19

- Other Key Principles: Include Confidentiality (Principle II), Professional Responsibilities and Workplace Standards (Principle III), Working in a Culturally-Diverse World (Principle IV), Assessment (Principle V), E-Therapy, E-Supervision, and Social Media (Principle VI), Supervision and Consultation (Principle VII), Resolving Ethical Concerns (Principle VIII), and Publication/Communications (Principle IX).19 The inclusion of a specific principle for technology reflects its growing importance.19

APA (American Psychological Association) Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct (2002, amended 2010)

The APA Ethics Code is foundational for psychologists, many of whom work in addiction treatment.83

- Structure: It comprises an Introduction, Preamble, five aspirational General Principles (Beneficence and Nonmaleficence, Fidelity and Responsibility, Integrity, Justice, Respect for People’s Rights and Dignity), and enforceable Ethical Standards.83 The code clarifies it is not intended, in itself, to be a basis for civil liability.83

- General Principles: These principles guide psychologists toward the highest ethical ideals, emphasizing striving to benefit clients and do no harm, establishing relationships of trust, promoting accuracy and honesty, ensuring fairness and justice, and respecting the dignity and worth of all individuals, mindful of diversity.83

- Relevant Ethical Standards: While the full text of specific standards was not available in the provided research 83, the code’s structure indicates standards covering key areas pertinent to this report: Resolving Ethical Issues (Standard 1), Competence (Standard 2, including boundaries of competence), Human Relations (Standard 3, including avoiding harm, multiple relationships [3.05], conflict of interest [3.06], informed consent [3.10]), Privacy and Confidentiality (Standard 4), Record Keeping and Fees (Standard 6), and Therapy (Standard 10, including informed consent to therapy [10.01], sexual intimacies with current clients [10.05], and sexual intimacies with former clients [10.08]).83

ACA (American Counseling Association) Code of Ethics (2014 Revision)

The ACA Code governs professional counselors, another significant group in addiction treatment.17

- Core Principles and Values: The code is based on principles of autonomy, nonmaleficence, beneficence, justice, fidelity, and veracity.17 It emphasizes that trust is the cornerstone of the counseling relationship and highlights the responsibility to respect client privacy and confidentiality.17

- The Counseling Relationship (Section A): This section mandates avoiding harm (A.4.a).17 It prohibits sexual/romantic relationships with current clients, their partners, or family members (A.5.a) 17 and prohibits counseling individuals with whom the counselor had a previous sexual/romantic relationship (A.5.b).17 A strict 5-year prohibition applies to sexual/romantic relationships with former clients, their partners, or family members, with a requirement for documented forethought regarding potential exploitation or harm if considered after that period (A.5.c).17 Counselors are also prohibited from counseling friends or family members if objectivity is compromised (A.5.d).17 Informed consent is detailed as an ongoing process requiring specific information disclosure (purpose, risks, benefits, counselor qualifications, confidentiality limits, fees, etc.) using developmentally and culturally appropriate communication (A.2).17 Maintaining accurate and timely client records is also required.17

- Other Key Sections: Include Confidentiality and Privacy (Section B), Professional Responsibility (Section C), Evaluation, Assessment, and Interpretation (Section E), Supervision, Training, and Teaching (Section F), Research and Publication (Section G), Distance Counseling, Technology, and Social Media (Section H), and Resolving Ethical Issues (Section I).17 The dedicated section on technology and social media highlights the need for specific guidance in these areas.17

NASW (National Association of Social Workers) Code of Ethics (2021 Revision)

The NASW Code is the primary ethical guide for social workers, who play vital roles in addiction services.87

- Core Values and Principles: The code is built upon six core values: Service, Social Justice, Dignity and Worth of the Person, Importance of Human Relationships, Integrity, and Competence.18 The corresponding ethical principles guide practice. The 2021 revision notably added language emphasizing professional self-care under the value of Integrity and updated the standard on Cultural Competence.18

- Ethical Standards (Responsibilities to Clients – Section 1): This section details numerous standards. Commitment to clients’ well-being is primary (1.01).18 Client self-determination must be respected and promoted, limited only by risk of serious harm (1.02).18 Valid informed consent is required, covering purpose, risks, limits, costs, alternatives, and right to refuse/withdraw (1.03).18 Competence requires practicing within one’s training and seeking appropriate education for new areas (1.04).18 Conflicts of interest must be avoided or managed prioritizing client interests (1.06a).18 Dual/multiple relationships with current or former clients are prohibited if there’s risk of exploitation or harm; unavoidable ones require careful boundary setting (1.06c).18 Specific guidance addresses avoiding personal communication via technology and boundary confusion via social media (1.06e, 1.06f).18 Privacy and confidentiality must be rigorously protected, with limits explained (1.07).18 Sexual relationships with current clients (1.10a) and clients’ relatives (1.10b) are prohibited.18 Sexual relationships with former clients are strongly discouraged due to potential harm, with the burden on the social worker to prove non-exploitation if such contact occurs, considering multiple factors (1.10c).18

Cross-Cutting Themes and Implications

Analysis across these national codes reveals significant consensus on core ethical mandates. The prohibition against sexual relationships with current clients is universal and absolute. Strong restrictions govern relationships with former clients and relatives. The potential harm of non-sexual dual/multiple relationships is consistently recognized, with a mandate to avoid them if exploitative or impairing, and to manage unavoidable ones with extreme care, prioritizing client welfare through informed consent, consultation, and clear boundaries.

Furthermore, the evolution of these codes, particularly the more recent revisions by NAADAC, ACA, and NASW, demonstrates an increasing focus on the ethical challenges posed by technology. Specific standards now address informed consent for telehealth, maintaining confidentiality in electronic communications, and navigating the complex boundary issues arising from social media interactions.17 This reflects a necessary adaptation by the professions to ensure ethical principles remain relevant and protective in an increasingly digital practice environment.

VII. U.S. Legal Precedents and Civil Liability

Ethical breaches in addiction recovery settings can lead not only to professional sanctions but also to significant legal consequences, primarily through civil lawsuits seeking damages for harm caused to clients. Understanding the common legal claims, liability standards, and trends is crucial for both providers seeking to mitigate risk and individuals seeking redress.

Common Causes of Action

Lawsuits against rehabilitation centers and individual providers typically allege failures in the duty to provide safe and competent care. Common legal claims include:

- Negligence/Malpractice: This is the most frequent basis for lawsuits.21 It alleges that the facility or provider failed to meet the accepted standard of care that a reasonably prudent professional or facility would have provided under similar circumstances, and that this failure directly caused harm to the patient.35 Examples include:

- Improper assessment or treatment planning.36

- Inadequate care during detoxification or withdrawal management.36

- Failure to adequately monitor patients’ physical or mental status.35

- Medication errors (wrong drug, wrong dose, failure to manage interactions).34

- Premature discharge without adequate planning or support.37

- Sexual misconduct, which is generally considered a per se breach of the standard of care.21

- Negligent Supervision, Hiring, or Retention: Facilities can be held liable if they fail to exercise reasonable care in hiring, training, supervising, or retaining staff members, and a client is subsequently harmed by that employee’s foreseeable misconduct or incompetence.34 This requires demonstrating that the facility knew or should have known of the risk posed by the employee.

- Premises Liability: This involves injuries sustained due to unsafe conditions on the facility’s property, such as slip-and-fall accidents caused by wet floors or poor maintenance, inadequate lighting, broken locks, unsanitary conditions (e.g., mold, pest infestations), or insufficient fire safety measures.34

- Failure to Protect or Supervise: This claim arises when inadequate supervision or failure to implement appropriate safety protocols leads to client harm, such as assaults by other patients, self-inflicted injury or suicide, or preventable overdose or relapse occurring within the facility’s care.34

- Wrongful Death: If a patient dies as a result of negligence or misconduct by the facility or its staff (e.g., due to unsupervised overdose, suicide linked to inadequate care, fatal medication error), the patient’s surviving family members or estate may file a wrongful death lawsuit.37

- Breach of Confidentiality: Unauthorized disclosure of protected health information can lead to legal action, particularly given the strict protections under HIPAA and 42 CFR Part 2.

- Fraud or Misrepresentation: Facilities may face lawsuits based on deceptive marketing practices, such as falsely advertising services, success rates, or credentials.36

Establishing Legal Liability

To succeed in most civil lawsuits against a recovery center, particularly those based on negligence or malpractice, the plaintiff (the injured patient or their representative) must typically prove four key elements, often referred to as the “Four Ds” 92:

- Duty: The plaintiff must establish that the treatment facility or provider owed them a duty of care. This duty arises from the professional relationship and requires the provider to act with the skill and care reasonably expected of similar professionals or facilities.21

- Dereliction (Breach of Duty): The plaintiff must demonstrate that the provider or facility breached this duty by failing to meet the applicable standard of care through negligent actions or omissions.21 Establishing the standard of care and proving the breach often requires testimony from expert witnesses in the same field 21, although in cases of obvious misconduct (e.g., sexual abuse), the breach may be considered self-evident (res ipsa loquitur).92

- Damages: The plaintiff must show that they suffered actual harm or injury as a result of the breach. Damages can include physical injuries, emotional or psychological trauma (pain and suffering), medical expenses (past and future), lost wages or earning capacity, and other quantifiable losses.20

- Direct Causation: The plaintiff must prove that the provider’s or facility’s breach of duty was the direct or proximate cause of the damages suffered.21

Vicarious Liability

A crucial legal doctrine in these cases is respondeat superior, or vicarious liability. This principle holds employers legally responsible for the wrongful acts of their employees if those acts were committed within the scope of their employment.90 This means a rehabilitation facility can be held liable for the negligence or misconduct of its counselors, nurses, or other staff, even if the facility itself was not directly negligent in that specific instance (though claims of negligent supervision often accompany vicarious liability claims). This doctrine is significant because facilities typically have deeper pockets and larger insurance policies than individual employees, making them a primary target in litigation seeking compensation.90

Legal Trends and Considerations

- Therapist Sexual Misconduct: Lawsuits arising from sexual exploitation by therapists are a recognized area of malpractice litigation.20 Courts generally view such conduct as a clear breach of the standard of care.21 While many cases settle out of court 20, establishing liability involves proving the four elements of negligence. Damages can be substantial, encompassing emotional trauma, costs of subsequent therapy, and lost income.20 Liability may extend beyond the individual therapist to the employing practice or institution, particularly if negligent supervision or retention can be demonstrated.20

- Suicide Liability: Facilities face potential liability if a patient’s suicide occurs under their care and can be linked to negligence, such as inadequate assessment of suicide risk, insufficient monitoring, or failure to implement appropriate safety precautions.37 A key legal question is often foreseeability – whether the facility knew or should have known about the suicide risk. Courts have considered whether a patient’s suicide constitutes a “superseding cause” that breaks the chain of negligence from the facility’s actions; in at least one California case, the court upheld a verdict against a facility, finding the suicide was not necessarily a superseding cause given the facility’s alleged negligence in supervision.94

- Proving Non-Physical Harm: While physical injuries are often easier to document, claims based on emotional or psychological harm resulting from negligence (e.g., relapse due to inadequate support, trauma from verbal abuse or neglect) are valid, though potentially more challenging to prove and quantify.90 Expert testimony is often crucial in linking the negligent conduct to the resulting psychological damages.21

- Statutes of Limitations: Victims must be aware of strict time limits (statutes of limitations) for filing lawsuits, which vary by state and type of claim (e.g., often 1-3 years for medical malpractice).34 Failure to file within the specified period generally bars the claim.

The potential for civil liability highlights the significant risks associated with ethical breaches and operational failures in addiction recovery settings. Liability extends beyond individual practitioners to the organizations themselves, encompassing not only direct clinical care but also hiring practices, staff supervision, facility maintenance, and adherence to safety protocols. The prevailing legal standard revolves around negligence – the failure to provide reasonable care – making adherence to professional standards, thorough documentation, and robust risk management practices essential for all recovery centers.

VIII. Why Ethical Breaches Undermine Addiction Recovery

Ethical violations in addiction treatment settings are not mere procedural missteps; they strike at the heart of the recovery process, actively undermining the psychological, emotional, and even neurobiological foundations necessary for healing and sustained sobriety. Understanding the mechanisms by which these breaches cause harm is essential for appreciating the critical importance of upholding ethical standards.

Violation of Core Therapeutic Principles

Effective therapy, particularly for addiction, relies on fundamental principles that are directly compromised by ethical misconduct.

- Trust: As repeatedly emphasized, trust is the bedrock of the therapeutic relationship.5 Clients, often burdened by past betrayals or trauma, must feel safe enough to be vulnerable, honest, and open to guidance. Ethical conduct – maintaining confidentiality, respecting boundaries, acting in the client’s best interest – is how trust is built and maintained. Conversely, ethical breaches like confidentiality violations, boundary transgressions, or exploitation shatter this trust, often irreparably.6 This destruction of trust can lead clients to withdraw from treatment, withhold critical information, or become resistant to the therapeutic process.6

- Safety (Physical and Psychological): Recovery requires an environment where clients feel both physically and psychologically safe.2 Ethical standards are designed to create and maintain this safety. Boundary violations, abuse (physical, sexual, emotional), neglect, or exposure to staff impairment create an unsafe, unpredictable, and potentially threatening environment. For individuals with histories of trauma, such violations can be profoundly re-traumatizing, reactivating past fears and defense mechanisms.2

- Autonomy and Dignity: Ethical practice respects the client’s right to self-determination, their capacity to make choices about their own life and treatment, and their inherent dignity and worth.6 Exploitative relationships, coercive practices, or the imposition of a provider’s personal values violate client autonomy.22 Disrespectful or demeaning treatment undermines dignity.6

- Beneficence and Non-Maleficence: These twin principles form the ethical core of healthcare: the duty to act for the benefit of the client (beneficence) and the duty to avoid causing harm (non-maleficence).17 Ethical breaches, by definition, either fail to prioritize the client’s well-being or directly inflict harm (emotional, psychological, physical, or relational), thus violating these fundamental obligations.8

Impact on the Therapeutic Alliance

The therapeutic alliance – the collaborative bond between therapist and client characterized by mutual trust, respect, and agreement on goals and tasks – is consistently shown to be a strong predictor of positive treatment outcomes across various therapies, including addiction treatment.28 Ethical breaches severely damage this alliance.

- Boundary violations can introduce confusion, mistrust, and conflict, leading to “alliance ruptures”.28

- Exploitation or betrayal makes genuine collaboration impossible.8

- When professionals model unhealthy relationship dynamics (e.g., blurred boundaries, manipulation), it contradicts the therapeutic goal of helping clients develop healthier interpersonal patterns.31

Without a strong therapeutic alliance, the client’s motivation, engagement, and willingness to undertake challenging therapeutic work are significantly diminished.

Introduction of Triggers and Increased Relapse Risk

Addiction is understood as a chronic, relapsing brain disorder involving significant alterations in neural circuits related to reward, motivation, stress response, and executive control (e.g., decision-making, impulse control).10 Recovery involves managing these altered circuits and developing coping mechanisms to prevent relapse. Ethical breaches can directly interfere with this process by introducing potent relapse triggers.

- Neurobiology of Relapse: Environmental cues (people, places, objects associated with past use), internal states (stress, negative emotions like anxiety, depression, anger, boredom), and exposure to the substance itself can trigger intense cravings.9 These triggers activate the brain’s reward pathways (dopamine release) and stress circuits, often overwhelming the prefrontal cortex’s capacity for self-control.10 High levels of stress and negative affect are strongly associated with relapse vulnerability.9

- Ethical Breaches as Triggers:

- Emotional Destabilization: Inappropriate relationships, boundary violations, or experiences of exploitation inevitably cause significant emotional distress – confusion, guilt, shame, anger, anxiety, betrayal.8 These negative emotional states are well-established triggers for substance use cravings and relapse.9

- Increased Stress: Navigating the aftermath of an ethical violation – dealing with the emotional fallout, deciding whether to report, potentially engaging in complaint processes or litigation – introduces immense stress into a client’s life, depleting the cognitive and emotional resources needed to maintain recovery.9

- Modeling and Exposure: Staff who use substances with clients or exhibit impaired behavior directly model the problematic behavior the client is trying to overcome and can introduce powerful environmental cues and triggers.

- Erosion of Safety and Trust: The violation of trust and the loss of a sense of safety within the therapeutic environment can leave clients feeling hopeless, isolated, and less equipped to manage cravings or seek support when faced with triggers, thereby increasing relapse risk.6

Creation of Emotional Instability and Distraction from Recovery Goals

Ethical conflicts divert the client’s focus and energy away from their own recovery journey.7 Instead of working on understanding their addiction, developing coping skills, and rebuilding their lives, they become preoccupied with the problematic relationship, the ethical breach, or its consequences. The resulting emotional turmoil, confusion, and potential cognitive dissonance consume mental resources essential for engaging effectively in therapy and practicing relapse prevention strategies.8

Contradiction with Trauma-Informed Care (TIC) Principles

Given the high prevalence of trauma histories among individuals with SUDs 1, providing care that is trauma-informed is crucial. TIC involves recognizing the impact of trauma, understanding paths to recovery, integrating this knowledge into practices, and actively resisting re-traumatization.2 Ethical breaches fundamentally contradict TIC principles established by SAMHSA and other bodies 2:

- Safety: Boundary violations, abuse, and exploitation directly undermine the creation of a safe physical and psychological environment.96

- Trustworthiness and Transparency: Ethical misconduct inherently involves a betrayal of trust and often a lack of transparency.96

- Collaboration and Mutuality: Exploitative dynamics replace the collaborative partnership essential to TIC.96

- Empowerment, Voice, and Choice: Violations disempower clients, disregard their autonomy, and silence their voice.2

Because ethical violations often involve misuse of power, violation of boundaries, and betrayal – dynamics frequently present in past traumatic experiences – they carry a high risk of re-traumatizing clients.8 This can trigger PTSD symptoms, intensify addiction severity, and create significant barriers to recovery. Therefore, adherence to strict ethical standards is not merely good practice; it is an essential component of providing genuinely trauma-informed care.

In essence, ethical violations are not passive failures but active agents of harm in the recovery process. They damage the therapeutic relationship, create unsafe conditions, trigger neurobiological relapse mechanisms, destabilize clients emotionally, distract from recovery goals, and potentially re-traumatize vulnerable individuals. Upholding ethical standards is thus inextricably linked to the potential for successful client outcomes.

IX. Ensuring Client Safety: The Role of Oversight, Policies, Training, and Supervision

Preventing ethical violations and ensuring client safety in addiction recovery centers requires a proactive, multi-layered strategy that extends beyond individual good intentions. It necessitates robust systems of oversight, clearly defined policies, comprehensive training, effective supervision, and accessible reporting mechanisms. Failure in any of these areas can create vulnerabilities that allow ethical breaches to occur and harm clients.

Importance of Robust Ethical Oversight Mechanisms

Oversight functions at both internal and external levels to monitor compliance and address concerns.

- Internal Oversight: Facilities must establish and maintain effective internal systems. This includes implementing clear, accessible client grievance procedures, as mandated by Ohio law (OAC 5122-26-18), complete with designated Client Rights Officers (CROs) who can impartially investigate complaints.62 Regular internal audits of clinical records, billing practices, and adherence to policies are also crucial for identifying potential issues proactively.44